One-hundred and three years ago — as of Jan. 16, 1919 — something happened halfway across the country that would forever change Ridgewood and Glendale in a profound way.

On that date, Nebraska’s legislature approved what would become the 18th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: the prohibition of mass production and sale of alcoholic beverages. It was the 36th state to do so, and with three-fourths of the states having approved it, the amendment was ratified nationwide.

The 18th Amendment gave Congress the authority to enact what would become the Volstead Act, which would take effect Jan. 16, 1920 — one year to the date of the amendment’s ratification. The act defined what constituted an alcoholic beverage in the eyes of the federal government, and included limits on how much beer and wine could be produced for home consumption.

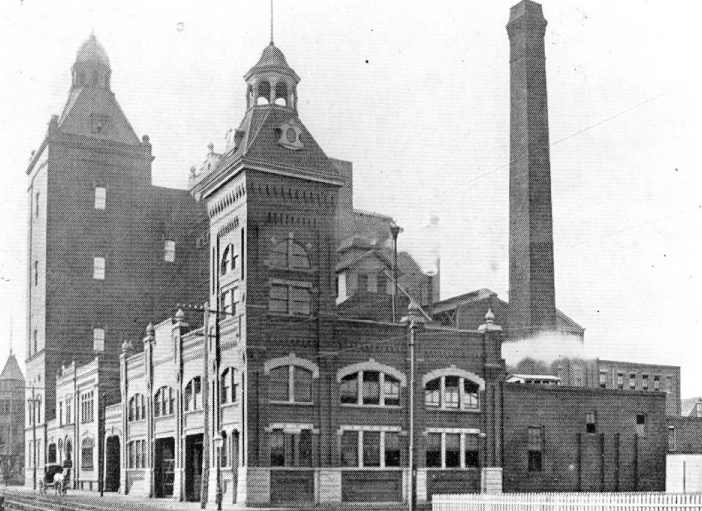

Prohibition would impact every corner of this country, but it had a particularly striking effect on Ridgewood and Glendale. Before Prohibition, the neighborhoods were home to many breweries that employed hundreds of local residents; restaurants, taverns and inns that served locally brewed beer; and a few of the remaining bucolic picnic parks that were popular among city dwellers for weekend getaways from urban life.

In the wake of Prohibition — which would be repealed in 1933 — many of those breweries, establishments and picnic parks were gone or slowly fading into history.

Why would Americans prohibit the mass production and consumption of alcoholic beverages? The amendment came out of the Temperance Movement; its followers believed that intoxication led to myriad social problems including poverty, violence and lewdness.

While the Temperance Movement’s origins date back to the early 1800s, the movement picked up steam in the years immediately before and after the United States’ entry into World War I, which occurred in 1917. Many state legislatures had already passed their own forms of Prohibition legislation prior to the 18th Amendment’s ratification.

The aforementioned Volstead Act defined an alcoholic beverage as being one with 1/2 of 1 percent or more alcohol by volume (which is about 4/10 of 1 percent by weight). The Volstead Act permitted a limited amount of beer and wine to be produced for home consumption.

In 1918, American breweries produced 32 million barrels of beer; in 1919, with the breweries closing at the end of April, just 7.4 million barrels were made. Local brewing companies either significantly altered their recipes, recreated their entire business or simply shut down.

S. Liebmann’s Sons, which brewed Rheingold beer, and Obermeyer & Liebmann switched to producing soft drinks and near beer, with the latter being classified as a cereal beverage with less than 1/2 of 1 percent alcohol by volume.

Near beer was a relatively bland beverage and had limited appeal. In 1921, a number of consumers tried it and the equivalent of 9.7 million barrels was sold. However, by 1932, which was the last full year of Prohibition, it had declined to 2.7 million barrels. Near beer was similar to today’s so-called non-alcoholic beers which actually have a small amount of alcohol.

In 1924, Obermeyer & Liebmann was merged into S. Liebmann’s Sons, and the name of the parent company was changed to Liebmann Breweries Inc. Rheingold would be resurrected following Prohibition.

Diogenes Brewery, which had been located at the corner of Wyckoff Avenue and present-day Decatur Street, ceased operations once Prohibition took effect. The company tried to rebrand itself the Malt-Diataste Company. It produced malt syrup for home brewers, as the Volstead Act permitted such practice.

Another brewery that succumbed to Prohibition was the Frank Brewery located at the corner of Cypress Avenue and Hancock Street. The City Brewing Company would reactivate the business following Prohibition, but it would only last 17 years thereafter.

The changes on the local brewing scene also impacted businesses at local restaurants and taverns. Samuel Liebmann’s Sons Brewing Company had operated a saloon at 770 Onderdonk Ave. in Ridgewood to serve their beer which ultimately closed due to Prohibition. It found a second life after Prohibition’s repeal as Two Kioodles bar.

The Brockmann Brothers’ hotel and saloon at the corner of Myrtle Avenue and present-day 69th Place in Glendale converted their business to the Brockman Brothers Restaurant and survived Prohibition.

But Prohibition served as the death knell of the local picnic park. In the years leading up to Prohibition, these parks — which offered a relaxing, natural place to get away from the hustle and bustle of the city — were disappearing as Ridgewood and Glendale were developed into residential communities. One could argue that it was only a matter of time before the picnic parks would disappear, but it’s not an exaggeration to conclude that Prohibition certainly accelerated their demise.

Take, for example, Schmidt’s Woods, which covered 26 acres of Glendale off of what is today the intersection of Myrtle Avenue and 83rd Street. It was a place designed for families looking to hold big gatherings on weekends. The park included swings for children, a substantial number of picnic tables and benches, baseball fields and even a soccer field.

One of the big sellers at Schmidt’s Woods was, naturally, beer. An eighth-barrel of Welz and Zerwick lager cost $1 and was delivered by an attendant to the family picnic table. Sometimes free pretzels were provided; the salt, of course, kept the adults thirsty for more beer.

It wouldn’t be long after Prohibition hit that Schmidt’s Woods would become a memory. It closed in 1925, one of the last of the Glendale picnic parks to shut down. The land was redeveloped for housing.

Another picnic park that died during Prohibition was Cypress Hills Park, located at the southwest corner of Cypress Avenue and Cypress Hills Street, which was a particularly popular attraction for the area’s German community. The park included “Banzer’s Lake,” a 600-foot long U-shaped lake that was perfect for summer boating and winter ice skating. After Prohibition took effect, Cypress Hills Park hung on, surviving on family outings and numerous functions held by local fraternal, benevolent and church organizations.

Cypress Hills Park closed in the late 1920s, and Banzer’s Lake was drained and filed in. Part of the land became used as cemetery land, while the remaining portion was included in the construction of the Interboro (present day Jackie Robinson) Parkway.

While Prohibition’s supporters had good intentions, it turned out that the ban on alcohol paved a road to a different kind of hell: organized crime. Mobsters began lucrative bootlegging operations, smuggling alcohol into the United States for sale at local speakeasies. More than 100,000 such underground bars popped up across New York City during Prohibition. The sense of lawlessness, combined with economic losses felt locally and nationwide because of the ban and the Great Depression, led to the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1933 — which repealed the 18th Amendment.

It wasn’t long before the suds flowed in Ridgewood again. In May 1915, the Ridgewood Times reported that the City Brewing Company, at the former Frank Brewery, turned out 750 barrels of Tally-Ho Beer every day and had installed new storage tanks holding 290,000 barrels of beer. This enabled the company to produce 1,400 beer barrels every day by that October.

Ridgewood’s place in beer brewing wasn’t the same after Prohibition, but the neighborhood’s love of beer has never waned. The tradition lives on in the many micro-breweries that have popped up in our area in recent years.

If you have memories to share with us, send an email to editorial[@]ridgewoodtimes.com (subject: Our Neighborhood: The Way it Was) or write to The Old Timer, ℅ Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361. Any mailed pictures will be carefully returned to you upon request.