Just a few decades ago, if you walked down most streets in Ridgewood — particularly the area between Myrtle and Irving Avenues — you’d see block after block of textile mills and other industries. The hum of weaving machines was audible to anyone passing through the area on a busy work day.

Ridgewood was, at one point, home to hundreds of small textile mills that have disappeared from the scene — their plants and jobs shipped out to other states and countries as companies sought to cut costs.

For many years, these mills — along with other industrial factories that closed down for the same reason — remained vacant and fallow, like unused farmland. Some landlords chose to let the properties sit until new opportunities came along — namely, changes in zoning laws that would allow them to repurpose the factories for other uses.

Over the last decade, many of the former Ridgewood factories have been transformed into artist lofts and other apartments, accommodating the arrival of a new generation of residents. Many of these folks are young professionals who’ve come to the area in search of more affordable housing, close to the subway — both of which have always been abundant in the community.

These professionals brought with them a new vibrancy to Ridgewood; some of them opened up new cafes, workspaces and other businesses across town, bringing new life to the local economy.

Some longtime Ridgewood residents might bristle at all the change and their effects. Yet, if you look at the history of the neighborhood over the past 125 years, change and the arrival of new residents have been the constant trends.

The neighborhood has evolved many times over through the decades — but the most radical transformation occurred 120 years ago, at the dawn of the 20th century.

Hard as it is for many fellow old timers in Ridgewood to witness life without textile mills and other industries, it is even more difficult to imagine the community in a largely rural state.

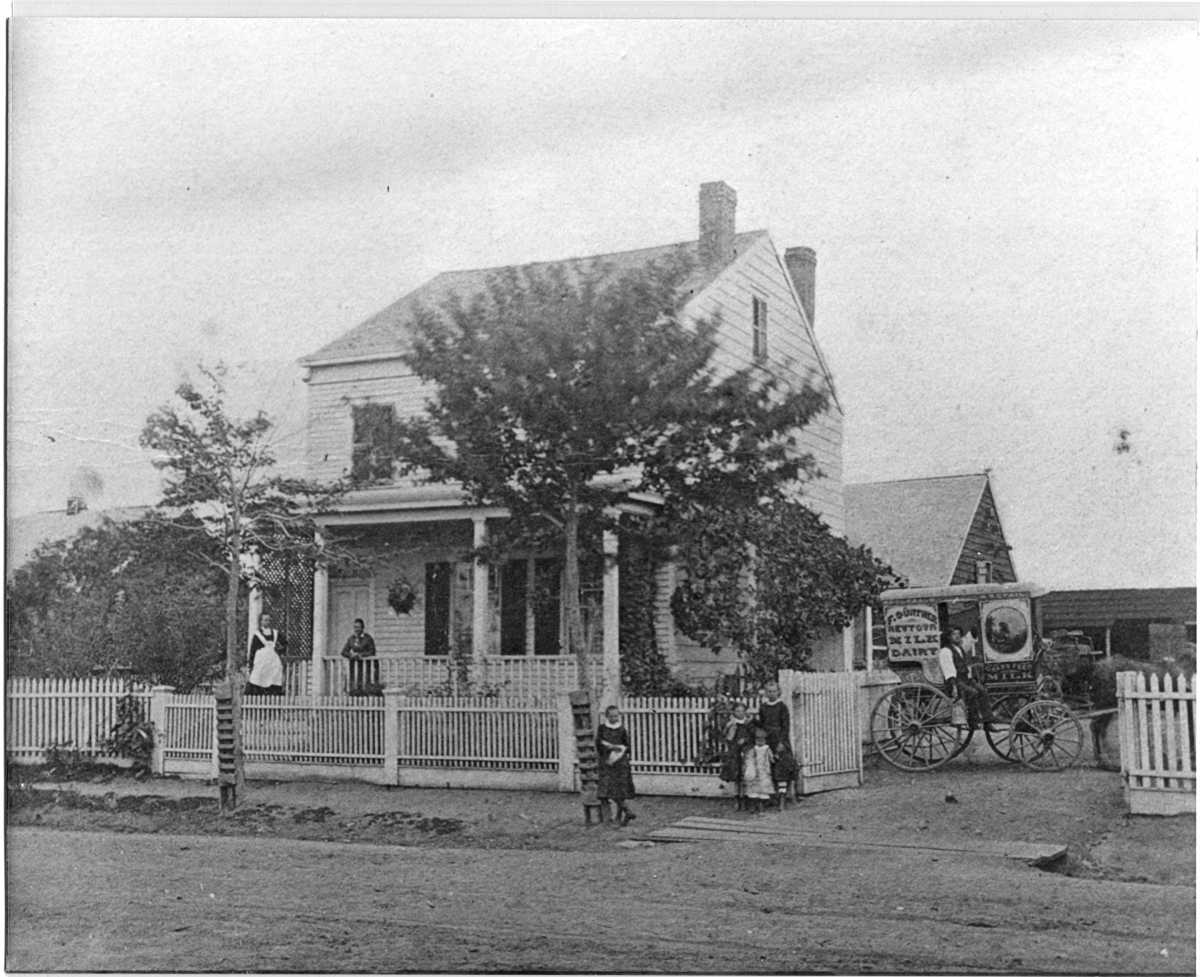

But that’s what our neighborhood was back in 1900 — bustling with family farms from one corner of the area to the other. Within 20 years, almost all of them would be gone — and a new urban community would rise in its place.

“The Great Building Boom” in Ridgewood was well documented in the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society’s 1976 book, “Our Community: Its History and People.” It’s out of print now, but The Old Timer is fortunate enough to have a copy on hand.

What follows is an excerpt from the society’s account of the birth of modern-day Ridgewood:

By 1900, a great wall of buildings had slowly crept eastward from Brooklyn and also from the north, and was ready to consume what was left of old Newtown Township. The builders looked with great anticipation at the almost flat and solid, good earth of Ridgewood. Here was a vast space to build in.

Many Germans who lived in Yorkville and in Williamsburgh were looking for greener pastures. Even in those days, Williams was turning into a slum area. Yorkville in Manhattan was congested. Their inhabitants had their eyes on something brand-new and sparkling, and the builders were ready to accommodate them.

Much of the population of nearby Brooklyn and what was Ridgewood at that time was German. It stood to reason that those who would fill up the vacant spaces would also be German. So when the building began, there wasn’t any great time lost on sentimentality.

Between 1900 and 1912, the Wyckoff, Van Sise, Fleckenstein, Meyerrose and Debevoise farms all disappeared and were speedily overlaid with cement and brick.

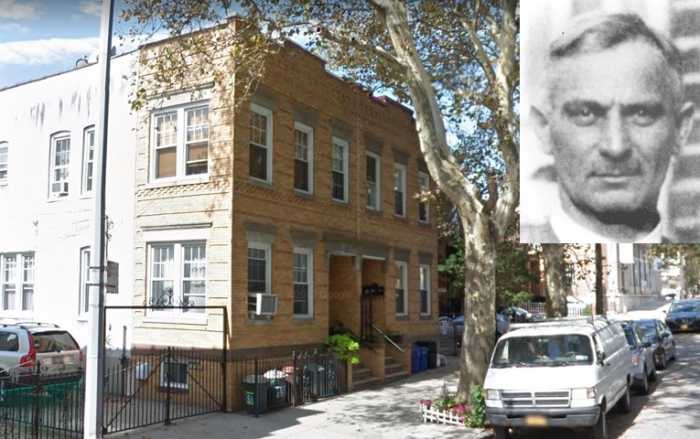

The early Ridgewood builders were a group of men who specialized in the Greater Ridgewood area — but that isn’t surprising, considering that builders usually concentrate within certain neighborhoods. These Ridgewood builders were practical men, most of whom had probably been raised on farms themselves.

The people who purchased their houses were themselves mostly immigrants, as were the tenants who rented apartments within the new structures. Most had come from farms. They’d known farms all their lives. So who needed a farm anymore?

The city was becoming the thing: a beautiful brick building with air shafts and dumbwaiters and modern plumbing, and a private stall in the cellar for storing one’s equipment. A city apartment, especially a new one, was a sign of prestige.

There was a nucleus of about 50 builders who handled most of the construction. Some built only a mere handful of homes, simply dabbling at the fringes of a huge market, but others built them by the hundreds.

Names like George Loeffler, John Fisher, Richard Weber, Louis Warmers, the Mathews Brothers and many others rang high and mighty in local real estate circles. These men of enterprise also helped to create that secondary market that goes with building construction.

For the multiple dwellings consumed an endless stream of kitchen sinks and cabinets, dumbwaiters, stone stoops, ironwork and, of course, all of the usual interior personal possessions that fill up an apartment. Many of these items were made in nearby factories, and the supply could barely keep up with the demand.

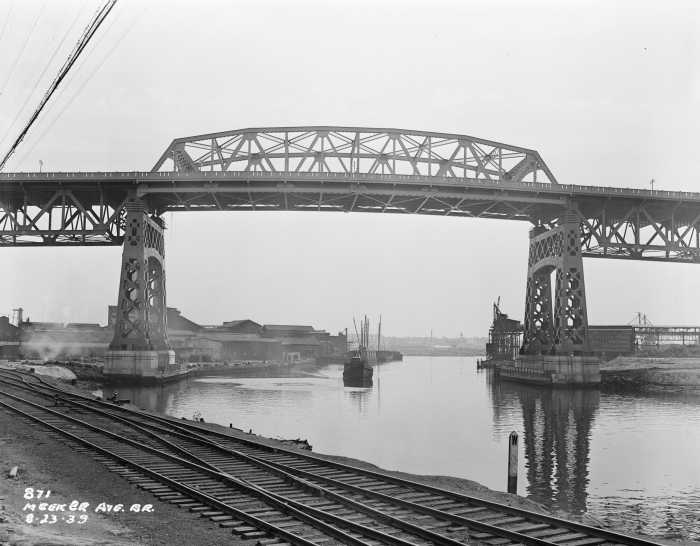

All of this building also generated street development, like cement sidewalks, cobblestone streets and sewers. One can easily see what building growth did for the economy of that era.

The impact on the ecology at that time was fantastic. Where crops had once grown profusely, and gentle winds had blown over flat, grassy fields, there was suddenly nothing but stone and concrete. Twenty- and thirty-foot-high buildings, block after block of them, stopped dead any ambitious wind, heading anywhere, so that Ridgewood became almost a windless city.

What had once been a land of picnic parks and clapboard farmhouses surrounded by oaks, birches and elms also came close to being a treeless city. Only in the 1970s have various streets of Ridgewood been revitalized with some greenery by the conducting of tree-planting campaigns.

There is, of course, one constant reminder of Ridgewood’s rural past today: the Vander-Ende Onderdonk House, at 1820 Flushing Ave., close to the Ridgewood/Bushwick border.

The house dates back to the Dutch settlement of New Netherlands, more than 400 years ago. During the 20th century, it was converted into part of a factory as the area transformed into a heavy industrial area.

But by the 1970s, the colonial farmhouse was vacant and falling into disrepair. The Greater Ridgewood Historical Society was formed, in large part, as an effort to save and restore the Onderdonk House as a landmark.

Today, the Onderdonk House — the campus encompassing nearly a full city block — hosts numerous events celebrating Ridgewood’s history and culture. The house has become a museum documenting the Onderdonks who once lived there and many related artifacts connected to our local history.

We should also point out, alluded to in “Our Community,” efforts have taken place over the last 40+ years to add trees across Ridgewood. Those efforts, in recent decades, have been spearheaded by the Ridgewood Property Owners and Civic Association, which has held annual surveys and letter-writing campaigns imploring local elected officials and the city’s Parks Department to add street trees across the neighborhood.

During our research, in fact, we came across an article in the Ridgewood Times published on April 15, 1982, which documents the tree-planting effort. Paul Kerzner, who was then RPOCA president (he would serve many times as the civic group’s boss over the next four decades), spoke of a letter he sent to then-City Councilmen Arthur Katzman and Walter Ward requesting funding for tree-planting.

Ward, the report noted, wrote to then-Borough President Donald Manes “urging that the Capital Budget for 1983 allocate funds for more tree planting in Queens. Ward reaffirmed Kerzner’s conviction that tree planting on “both residential and commercial” streets is an important implement in reassuring “residents of the stability of their neighborhood and aids in raising property values of their community.”

* * *

If you have any remembrances or old photographs of “Our Neighborhood: The Way It Was” that you would like to share with our readers, please write to the Old Timer, c/o Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361, or send an email to editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com. Any print photographs mailed to us will be carefully returned to you upon request.