It is a typical Tuesday evening in the Times Square—42 St subway station. Subway trains continue their ceaseless beat across the city while commuters dart in every direction to catch their rides. Amid this chaotic labyrinth of underground passages and platforms, newly arrived immigrants line the walkways, selling candy and fruit in a determined effort to carve out a living.

The challenges faced by these migrant vendors are almost insurmountable, as they strive to make a living by selling often-overlooked products to commuters who rarely glance up from their phones while navigating subway cars and platforms. Their efforts underscore the harsh circumstances that have driven them to this precarious line of work.

For many undocumented immigrants, particularly those with young children, vending on public transportation becomes a natural choice, drawing on a common practice among the poor in several Latin American countries.

But it is a world fraught with danger and risk. Suspicion is understandably rife among the sizeable population of migrant vendors scattered throughout the subway system, many of whom face threats of physical violence and police prosecution. Many vendors have also expressed fears over the incoming Trump presidency and have detailed plans to stop vending after Jan. 20, cutting off their only source of income.

On this particular Tuesday evening, eyes dart from side to side in search of NYPD officers patrolling the Times Square station at rush hour out of fear of being caught vending without a permit.

Andrea, an Ecuadorian immigrant vending in the Times Square concourse, constantly scans the passages leading off the concourse, ready to move her merchandise at a moment’s notice if she spots a patrolling officer.

The consequences of being caught by the NYPD can be severe. Melida, a Honduran immigrant who entered the US illegally two years ago, has received several $50 fines after being caught selling fruit in the Grand Central – 42 St station. On some occasions, she said, NYPD officers have also destroyed her merchandise.

Such penalties can be detrimental to vendors. On a good day, Melida makes profits of between $70-100 selling fruit in the Grand Central subway station, working up to 11 hours.

But trouble with the cops is by no means the only source of danger and suspicion for migrant vendors.

Ana, an undocumented migrant from Peru vending at the Bryant Park – 42 St station, said she was assaulted by a homeless individual living in the Bryant Park – 42 St station because she refused to give him free food, stating that the man grabbed her wrist so violently that she required medical treatment.

Fights sometimes break out between rival vendors over territory. On this particular Tuesday evening in the Bryant Park—42 St station, two vendors standing directly opposite each other became involved in a heated argument over space. The argument only stopped when a well-meaning MTA official from a Latino background intervened and informed them that he would be forced to report them if they continued.

Maria, an Ecuadorian woman selling churros and candy on a platform in Bryant Park, said she previously had to seek medical treatment after suffering severe bruising to her back during a previous encounter with the same vendor.

It is, perhaps, only natural that heated arguments arise between competing vendors when so much is on the line. Maria’s husband Luis revealed that he makes between $70-80 on good days when he has no competition. He said he makes considerably less when he has to compete with a vendor operating in close proximity.

Matthew Shapiro, legal director at the Street Vendor Project, a non-profit advocating for street vendor’s rights in New York City, said many subway vendors are vulnerable to danger because they spend most of their day in public-facing positions.

“Vendors are vulnerable because of who they are,” Shapiro said. “They’re working in public spaces. Crimes against businesses happen, even when they have storefronts.”

Many vendors selling candy and other items in the New York City subway system are doing so because they are unable to find other work due to a lack of childcare for those young children, according to a June 2024 survey by migrant advocacy group Algun Día.

Around 80% of vendors surveyed by Algun Día said they lacked sufficient child care to seek work in other fields. Meanwhile, 31% of those surveyed are living in one of the 200 migrant shelters scattered across the city, where they are not permitted to leave their children unsupervised, and a further 32% of vendors share accommodation with people they do not know or do not trust to mind their children.

The survey additionally found that almost 100% of vendors were unaware that existing programs help cover the cost of childcare, including Promise NYC, a city program providing access to childcare for low-income families.

The program, first launched in January 2023, has cared for over 600 children since its inception but is drastically underfunded to cope with current demand, according to Algun Día co-founder Monica Sibri. Sibri called on the Adams administration to significantly increase funds for the program.

“Promise New York City is one of those programs that’s helping, but it’s a program that is not meeting demand because the demands are exceeding the number of seats available,” Sibri said.

“It’s really heartbreaking. We walk the subways, we listen to the stories, and really come face to face with the reality,” she added. “It’s scary to see that our city has not given the proper attention to a program that would mean we no longer have it as an issue in our city.”

Elena, an Ecuadorian vendor with a variety of candy bars in her hands and her seven-month-old baby strapped to her back, said she was left with no other choice but to start selling candy on the subways and in stations.

Elena said she started working as a vendor to support her child but added that she sometimes faces scrutiny from commuters about her decision to bring her child along with her.

“Sometimes people just walk up to me and ask why I have my child with me,” Elena said. “But sometimes people are very generous [when they see her working with her child].”

Sibri noted that 83% of respondents to the Algun Día survey said they would pursue a different line of work if they had access to childcare, stating that former subway vendors who have received access to childcare have gone on to find jobs as cleaners or laborers, providing a more reliable source of income.

Other migrants began working as vendors for other reasons.

Melida revealed that she started working as a subway vendor after being exploited in her previous job, stating that her former employer withheld her pay, knowing that she would not report the offense given her immigration status.

Assembly Member Catalina Cruz, representing District 39, which includes parts of Corona, Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights, urged commuters to see the “big picture” when they see undocumented migrants selling candy on the subway.

Cruz, a former undocumented immigrant who represents a district where many subway vendors live, said most vendors are working on the subways out of necessity and added that many vendors are victims of a “vicious cycle of need and abuse,” stating that employers often exploit an individual’s immigration status and leave them with no choice but to seek a living as a vendor.

“Folks need to work and other folks are abusing that need,” Cruz said. “Think about how desperate these people must feel that they are not only doing it in possibly dangerous situations, but they’re doing so while joined by their children. We’ve got folks who are doing this out of complete desperation.”

State Sen. Kristen Gonzalez, a native of Elmhurst who represents parts of Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens, said the city owes it to vendors to ensure that they are treated fairly.

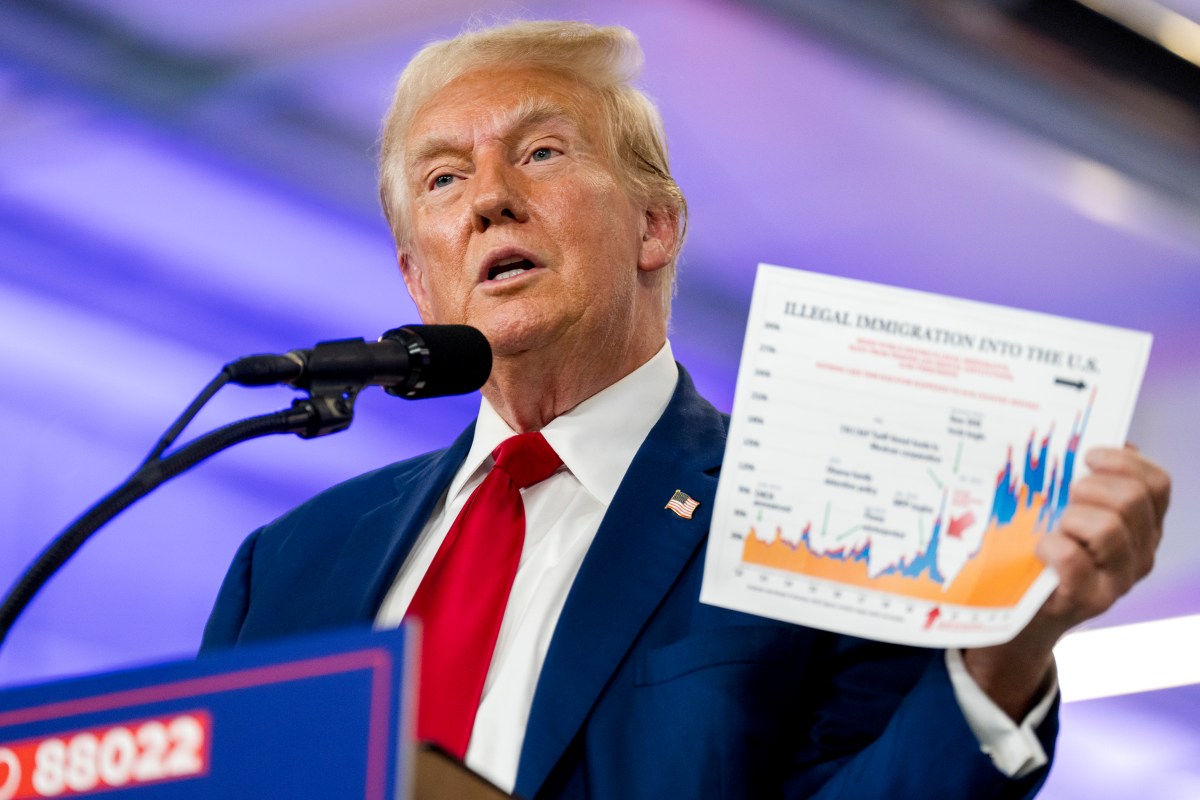

Many vendors expressed fear ahead of President-elect Donald Trump’s second term in office, stating that their work will mark them as easy targets for immigration officials once Trump takes office on Jan. 20.

Maria and Luis said they cannot bear to think about deportation because they still have unpaid debts related to their travel from Ecuador to the US and they cannot face returning home without repaying them.

Ana said she plans to stop vending on the subways if she hears of a crackdown on undocumented immigrants in the city following Jan. 20.

Meanwhile, Elena said she plans to stop selling goods come Jan. 20 out of fear of being apprehended.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do, especially in the winter.”

Cruz, meanwhile, said she is concerned for subway vendors who plan to stop vending after Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20.

“Hearing something like that makes me very concerned for these folks,” Cruz said. “How are they going to eat? How are they going to pay rent? Where are they going to live?”

Shapiro, on the other hand, said the “chilling effect” of Trump’s proposed immigration policies could severely impact undocumented immigrants who have come to rely on vending since arriving in New York City.

Trump has promised the “largest deportation” in American history when he returns to the Oval Office, but Shapiro believes that such campaign promises will have a negative impact on undocumented migrants working as subway vendors whether Trump carries out his proposals or not.

“Vendors are definitely more fearful, and I think they have a right to be,” Shapiro said. “If you get arrested, then your fingerprints go into the database that’s available for ICE regardless of our sanctuary city policies… Most vendors are not arrested, but sometimes they are. So if I was a vendor, I would be more concerned.”

Gonzalez believes immigration advocates need to take steps to protect undocumented migrants from the incoming Trump administration.

“We are still waiting to see exactly how the Trump administration will begin targeting immigrant communities, but I do think we need to take them at their word that that is exactly what they’re going to do,” Gonzalez said.

Sibri, meanwhile, said that a number of vendors have told Algun Día that they will stop operating in the subway system following Trump’s inauguration, stating that the number of vendors working in subways will drop dramatically after Jan. 20. Sibri predicted that the majority of vendors will cease operating in the subway out of fear of apprehension and deportation under the new administration.

Subway vending, for all its dangers and risks, has become integral to Elena’s life in New York City, like many other undocumented migrants who have arrived in the city in recent years.

Elena said life in America has been much more difficult than she anticipated before leaving Ecuador and added that a job as a subway vendor, with its lack of healthcare and a reliable income, makes it difficult to make ends meet. However, she said it still provides her with just about enough to provide for her young child and still represents an improvement compared to her life in Ecuador, where everyday essentials such as power and running water were by not a guarantee.

Sibri commented that the $50 that a subway vendor may make in a typical day represents a significant improvement on what they could earn in their native countries and represents the American Dream to many undocumented migrants.

“Although they’re not making tons of money selling in the subway, they are able to afford to be able to pay for rent,” Sibri said. “Optimism is the only choice they have.”

Gonzalez pointed to her own story as a daughter of an immigrant family who became the youngest woman to ever be elected to the New York State Senate as proof of the American Dream and New York City’s power to improve the lives of its immigrant citizens.

“It’s only in a city as special as this that a story like mine can happen,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez added that making it easier for undocumented immigrants to obtain work permits could help subway vendors find a more reliable source of income while also alleviating issues such as wage theft that force undocumented immigrants into vending in the first place.

“I really would love to see the conversation around how we can get creative in making New York a good state that supports all immigrant New Yorkers,” Gonzalez said. “Allowing folks to work who are here and want to work is in the best interest of our state economy.”

Sibri, however, called on elected officials to encourage Mayor Eric Adams to include Promise NYC and other programs in the executive budget to provide as much support as possible to undocumented immigrants seeking to better their lot. She also called for elected officials to endorse the Social Work Workforce Act, which would repeal the requirement that applicants must pass an examination in order to qualify as a licensed master social worker. Sibri believes that the act would result in more bilingual social workers offering their services at shelters and other programs serving the migrant population.

Undocumented immigrants may find themselves in greater need of support than ever after Jan. 20, as fears surrounding the Trump presidency threaten to discourage them from continuing as subway vendors, cutting off a vital but challenging source of income.

A typical Tuesday evening in the Times Square—42 St subway station might look very different after Trump’s inauguration. While subways will still pulse through the city and commuters will continue their hurried journeys home, the familiar calls of vendors—who have become a staple over the past years—may vanish, silenced by yet another obstacle in their already difficult path.

*All names have been changed to protect the identities of the subway vendors interviewed in this article. This story was made possible with the assistance and contributions of the Emerald Isle Immigration Center, whose support and insights were invaluable in shedding light on the challenges faced by undocumented immigrants in New York City.