More than 200 migrants, including individuals with no criminal records, have reportedly been deported to El Salvador’s Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT), according to immigrant advocacy organizations.

The reports follow growing concern from legal aid groups and community advocates who say a number of deportations are being carried out without adequate legal review.

CECOT, a maximum-security facility opened by the Salvadoran government in 2023 to detain gang-related suspects, has faced international scrutiny for its mass incarceration practices and alleged human rights violations. It is unclear how many of the deportees sent from the United States have criminal backgrounds or gang affiliations. ICE does not typically disclose individual removal details unless a case involves criminal convictions or national security concerns.

Natalia Aristizabal, deputy director of Jackson Heights-based advocacy group Make the Road New York (MTRNY), said her organization has seen a rise in what they describe as “collateral arrests”—a term used when ICE detains individuals not originally targeted for enforcement.

“We’ve seen people picked up during enforcement operations and later deported, even when they have no criminal history,” Aristizabal said. “Many of them are long-time residents with legal status.”

Aristizabal, who was raised in Queens, said it is deeply concerning that due process rights, guaranteed to all individuals under the U.S. Constitution, regardless of immigration status, appear to be increasingly undermined in deportation cases.

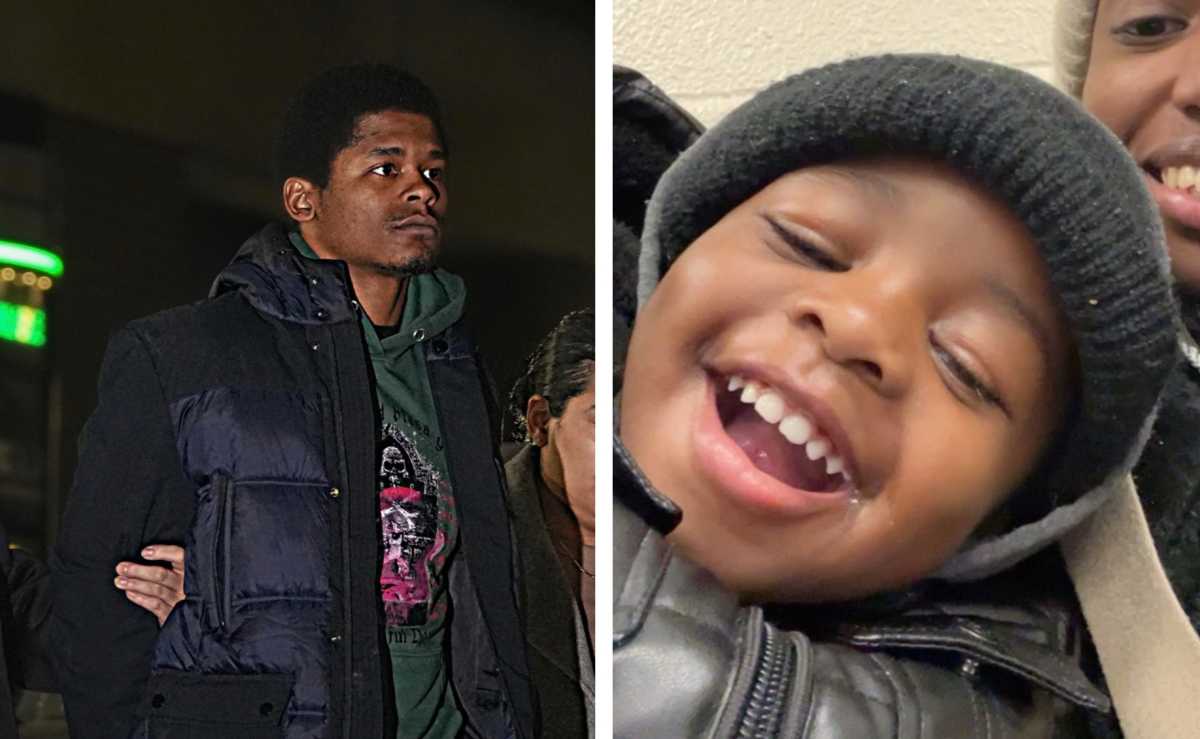

In one case handled by MTRNY, a Venezuelan man named Adrian, who holds Temporary Protected Status (TPS), was nearly deported earlier this year despite having no criminal record. His deportation was halted after his legal team filed a federal habeas corpus petition, which challenges unlawful detention. A judge ordered his release, and he has since returned to his home in New York, where he lives with his partner and child.

Advocates argue that such cases demonstrate the importance of legal safeguards in the immigration system, particularly for people who may have valid protection claims or residency status.

“Our worry is that people are being deported before they can access legal representation or understand their rights,” Aristizabal said. “In Adrian’s case, it took a plane malfunction and rapid legal intervention to stop what we believe would have been an unlawful deportation.”

The agency maintains that it prioritizes the removal of individuals who pose threats to public safety or national security, but it may also remove individuals who are present in the U.S. without lawful status.

Make the Road New York is currently lobbying for the passage of the New York for All Act, a state bill that would prohibit local law enforcement and government agencies from cooperating with federal immigration enforcement, except where required by law. Supporters say the legislation would help ensure immigrant access to public services without fear of detention or deportation.

Opponents of the bill argue that it could limit cooperation in cases involving serious criminal activity or gang violence.

Aristizabal said the organization believes the bill is a necessary safeguard as federal enforcement continues to evolve. “We need state protections that ensure people can live safely, regardless of their immigration status,” she said.

While some immigration lawyers have raised concerns about broader legal trends—including speculation about future limits on habeas corpus—no current federal proposals have been made public to repeal or restrict that legal right in immigration proceedings.

CECOT remains one of the largest prisons in the Americas, with a reported capacity of up to 40,000 inmates. Human Rights Watch and other international groups have raised concerns about indefinite detention, overcrowding, and due process violations in the facility. The Salvadoran government has defended the prison as a necessary response to gang violence.