In early February 1913, the Public Service Commission announced that it had granted the Brooklyn Rapid Transit permission to elevate the 1 1/2 mile section of the Myrtle Avenue Line from Wyckoff Avenue to just east of Fresh Pond Road in Ridgewood.

This was done to eliminate some of the congestion at the Ridgewood Depot, located at the corner of Myrtle and Wyckoff Avenues. Prior to this, the Myrtle Avenue Line operated as an elevated railroad as far east as Wyckoff Avenue, and then changed to ground level for the balance of the run to Metropolitan Avenue, with low-level stations at Seneca Avenue, Forest Avenue, Fresh Pond Road and Metropolitan Avenue.

From Wyckoff Avenue to Fresh Pond Road, the ground level railroad was fenced in on each side, and the only crossings were at the stations.

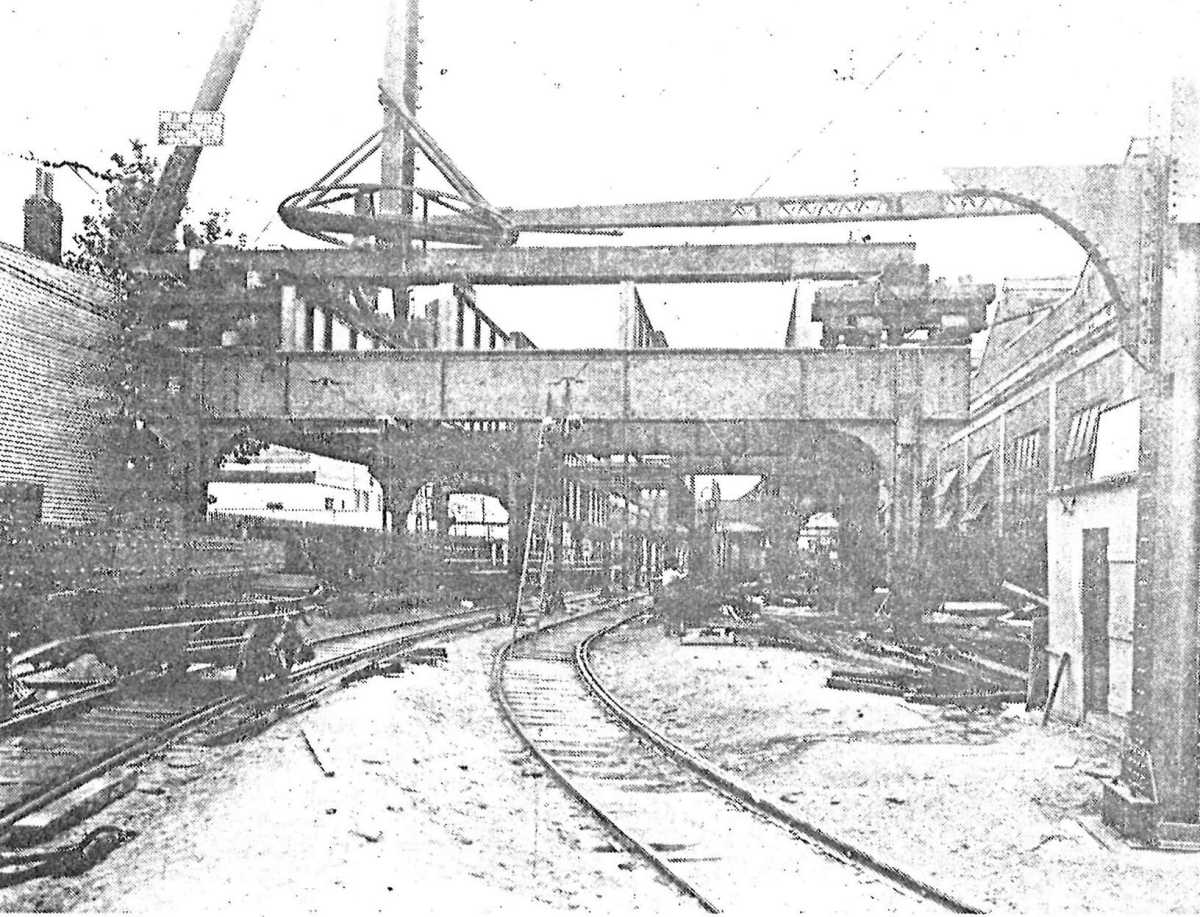

Shortly after receiving permission from the Public Service Commission, the BRT placed contracts with Frederick C. Burnham to build the 1 1/2 mile elevated railroad, but one of the conditions was that he had to do so while continuing to maintain service on the at-grade railroad to Metropolitan Avenue. This was done so as to not inconvenience local residents.

In turn, Burnham, who was based in Manhattan, hired various subcontractors such as Million Brothers Company to erect the steel and Empire Construction Company to lay the steel rails when the steel structure was completed.

Before work was started, a dangerous reverse curve led the trains from the elevated level to the ground level at Myrtle and Wyckoff Avenues, across the way from the car yards. This was eliminated and replaced by a single curve from Myrtle Avenue to Palmetto Street.

By May 1914, all of the concrete had been poured, and about 35 percent of the steel work had been completed. That September, the Empire Construction Company began laying rails.

On Feb. 15, 1915, the new section of the elevated Myrtle Avenue Line was placed into service. Shortly thereafter, the private right-of-way on the surface of Palmetto Street was once again available for electric trolley service. The Fresh Pond Storage and Service Yards were also enlarged on the east side of Fresh Pond Road at Putnam Avenue and Cornelia Street to hold 700 cars.

The BRT purchased additional land for $20,000 to accomplish this. The company also built a concrete clubhouse for the trainmen as the BRT began to switch some of the trolley lines that had formerly terminated at Ridgewood Depot over to the Fresh Pond Depot.

“The new line is a two-track road, and after leaving Ridgewood, has stations at Seneca Avenue, Forest Avenue and Fresh Pond Road, and it will make possible a substantial readjustment of the trolley and rapid transit services so as to relieve the congestion in the Ridgewood and East Williamsburg districts,” The New York Times reported in its Feb. 21, 1915 issue.

However, it wasn’t long before the BMT and the Myrtle Avenue Line were beset by one transit problem after another.

An editorial on the front page of Jan. 4, 1918 Ridgewood Times put it bluntly with the headline: PRESENT TRANSIT IS AN UNSPEAKABLE DISGRACE. A subheadline below noted that, “Instead of getting better, conditions are growing worse, and no improvement in sight.”

The editorial goes on to address grievances that some commuters in Queens might be able to relate to in the present day. In some respects, it’s the ultimate proof that the more things change, the more they indeed stay the same:

“Suffering live cattle transported from Western plains to the slaughtering pens of Chicago are herded together far more comfortably than are the human beings who are suffered to be jammed, rammed, crushed, crowded, dragged and pushed into the cattle cars of Brooklyn’s Ragged Transit system. No on knows whether they will come out with whole cloths or only a button, with limbs or without limbs.

The conditions are at the breaking point! No one can realize the horror of sitting back and forth at the rush hour except those who are compelled to subject themselves to the conditions that exist….

We say nothing for the moment as to the befuddled new rearrangement of this disgraceful transit system — its lack of accommodations, its miserable transfer arrangements from elevated to surface, its delays in working connections.

During the desperately cold days that we have had, it has been inhumane to say the least to compel people to wait at the different transfer points in Ridgewood for cars that seem to make their appearances less and less as each day goes by.

Here, too, is an issue that needs to be taken up and fought out to the finish by our local people until more surface cars are supplied.

But the vital thing at the moment that our people should fight against is the shortage of trains during the rush hours, and the disgraceful herding and packing of the young men and women who are compelled to travel back and forth daily in this manner….

DIVIDENDS MAY BE THE REAL EXCUSE but dividends can never be above human beings! Making money to the detriment, danger and possible death of the traveling public is a crime. WE ARE NOT GOING TO DIE YET IN ORDER THAT DIVIDENDS MAY LIVE!

THIS MUST BE CHANGED! MORE CARS MUST BE SUPPLIED! And Ridgewood should arise in such a powerful demonstration of protest as has never before been witnessed anywhere.

We are either cattle or worse than cattle, or we are human beings entitled to at least the simplest considerations of protection that a human being has reason to expect from the community in which he lives.”

The editorial mentioned dividends because the Brooklyn Rapid Transit — unlike today’s MTA, which has operated the M line and all other NYC subway lines since 1968 — was a for-profit company. The company was created in 1896 to consolidate rail line operations in Brooklyn and Queens. For a time, it was a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange.

While the BRT proved influential in building the city’s subway system, the company began to tank during the 1910s due to inflation and the start of World War I. The company began cutting back on services, and it caused much of the system to fall into disrepair.

The company took a further economic hit — and a severe public relations blow — following the derailment and crash of a train at the Malbone Street (later Empire Boulevard) station in Brooklyn on Nov. 1, 1918. It was one of the worst train crashes in American history, claiming 93 lives.

BRT soon fell into insolvency, but was restructured out of bankruptcy in 1923, becoming the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT). The BMT would later be sold to New York City in 1940, and the subway system was no longer a for-profit venture, but rather a public utility.

Additional information about the BRT can be found on NYCSubway.com.

***

If you have any remembrances or old photographs of “Our Neighborhood: The Way It Was” that you would like to share with our readers, please write to the Old Timer, c/o Ridgewood Times, 38-15 Bell Blvd., Bayside, NY 11361, or send an email to editorial@ridgewoodtimes.com. Any print photographs mailed to us will be carefully returned to you upon request.