He has been called “Good Sharma,” but Shri Om Dutta Sharma humbly brushes off the praise.

Sharma says that he simply did what he had to do - build a school for girls in his hometown of Doobher Kishanpur, India, and donate nearly half of his income as a cab driver to its funding and operations.

Referring to Mahatma Ghandi, Sharma said that all Hindus are taught to change the world for the better.

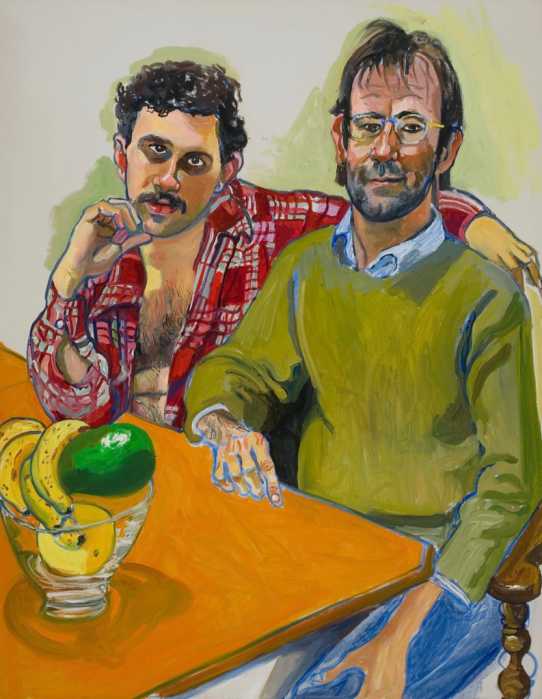

“We all have a moral, natural duty to do something,” he said, while sitting at the kitchen table of his Woodside home. “For me, it was easy to start something in the village where I was born.”

Born to poor farmers in a small town of 4,000, Sharma was taken in at age eight by the English brother of his grandfather, who brought several children to Bikanar, India for schooling. The man, a wealthy doctor, moved young Sharma more than 300 miles away from his family, whom he could not to speak to for eight months at a time. When the doctor died, Sharma moved back home at the age of 14 and began to make the three-mile trek each way to and from the nearest school.

“We had no choice,” Sharma said of his long walk to school.

Determined to continue his education, Sharma went on to high school and then college, which equates with 11th and 12th grades in the United States. For college, he moved to a town about 30 miles away and worked in a restaurant to pay for his schooling.

Later a friend helped him get a job as a tax clerk in New Delhi, where he met a wealthy African exporter, who hired him to travel to the United States - his first taste of the country that he would make his second home. At the same time, Sharma also met and married his wife, Krishner, and completed his law degree. His wife found a job as a nurse in the United States and urged Sharma to move here with her, and eventually he did. The couple settled in Woodside in 1974.

Although he had worked as a tax clerk and a lawyer in India, in New York, Sharma had trouble finding similar work. One day, while standing on a corner in Manhattan, he noticed how many people were hailing taxis and decided to become a cab driver. He applied one morning and he had a license by that evening.

Although in New York, a cabby's salary is relatively small, in India, the money could go a long way, Sharma said.

So when his mother passed away 13 years ago, leaving him with the farm where he was born, Sharma decided to do something to thank his parents for enduring back-breaking labor so that he could get an education.

“It is all because of my mother that I am sitting here in this world,” he said, slowly explaining how the idea for the school had taken root.

Sharma wanted to educate the girls in his hometown, who did not have the same opportunities that he had growing up.

“Girls can not go to the schools in the towns and the cities for lack of security and lack of availability, so I brought the school to them.”

He named the school in honor of his mother, Ram Kali, and told the townspeople that those most in need would be given first priority.

“These are your girls,” Sharma told the parents. “My duty is just to get them an education. You must make them wait to get married, so that they can learn.”

When it first opened, the school, the Sitaram Balkishan Ramkali Girls High School, drew 210 students, some who walked everyday from as far as two miles away, but the number has since swelled to nearly 450. At first, the students sat on the floor during their classes, but a wealthy donor gave Sharma money for desks and chairs. With $100 per month, he pays the local medic to give care - shots and medicine - to all of the girls free.

Now, with school's second class of students nearing graduation, Sharma said he is driven to create a nest egg for the all-girls school, led by 28 instructors. Once the school amasses a sizable savings, it can be run entirely off interest garnered each year, he said.

Funding comes primarily from Sharma's fares and tips, but media attention, including spots on CNN and the British Broadcasting Channel (BBC), has prompted several large contributions. Sharma has also been contacted about a longer documentary, which he said could be released as early as 2007.

In addition, money for the school is also raised in more traditional ways - the school has a grove of 50 mango trees, which are harvested for fruit to be sold at market every year.

Still, Sharma said that with more money he could do much more - build a boarding house for kids who travel from far away and offer specialty classes that could prepare the girls for work.

Computer and other technical training, he said, is still a long way off, for the town, where some people still don't have hot running water and electricity.

Sharma also feels he must instill in his sons a determination to continue the school.

“If I die tomorrow, who is going to fund the school?” the normally jolly cabby said thoughtfully. “It is their [my sons'] business after I'm gone.”

Sharma's sons, 28-year-old Braminick Bharadu, who is in the clinical stage of becoming a doctor, and 26-year-old Brasheel Bharadu, an accounting student at Queens College, said that they are up to the task.

“I love the idea,” Brasheel said, “Whatever he [Sharma] does, we always find a way to follow in his path.”