Woodhaven Boulevard dates back to the Colonial Era, when parts of it was known as Flushing Avenue and other parts referred to on maps as “the road to the landing” or “the road to the bay.”

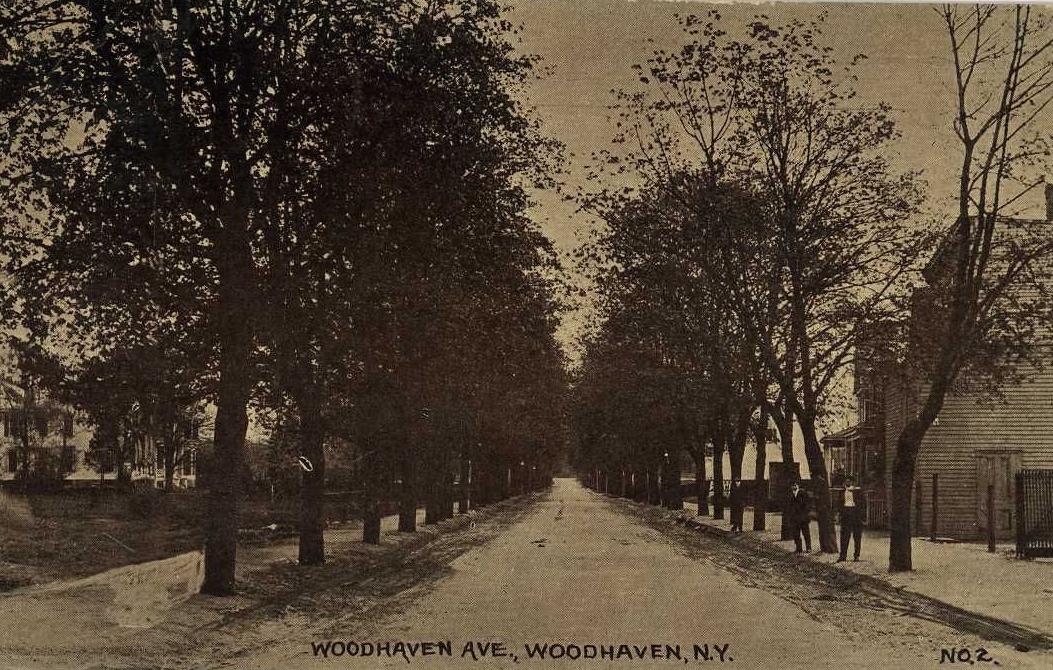

Around the start of the 20th century, Woodhaven Avenue (as it was now known) was a sleepy tree-lined dirt road that catered to horses and carriages. But with automobiles becoming a more common method of transport, people began to travel more and Woodhaven Avenue began to see a lot of traffic, particularly in the summer months when people began to flock to the Rockaways.

It is in the early 1920s that the city makes a strong push to widen Woodhaven Avenue. The Homestead Civic Association protested, citing the number of new homes that would need to be torn down. More important to the residents was the matter of who was going to pay for all of this.

At that time, the cost for major projects was directly assessed on property owners and depending on the project, it could be quite costly. Newspaper editorials of that era scolded the city for what was termed “confiscatory assessments,” projects where the cost was assessed locally, and the burden put on the local homeowner. In many cases, people lost their homes because they could not pay for the local streets and sewers that the city built.

The city was proposing that the bulk of the project to widen Woodhaven Avenue be assessed locally, paid for by the homeowners in Woodhaven.

“I live within a hundred feet of Woodhaven Avenue and I say right now it will be of no benefit to me,” one homeowner said at a public hearing. “Those who will derive the benefit will be the residents of Manhattan and the Bronx, not the people of Woodhaven.”

And so, the initial push to widen Woodhaven Avenue failed, but the battle lines were drawn and the fight would resurface on and off again for most of the next two decades.

In 1935, the city proposed creation of the Woodhaven Expressway, an elevated highway which would travel high over the homes of Woodhaven. The planned highway would elevate at Woodhaven, right before Myrtle Avenue, and return to ground level where Woodhaven runs into Cross Bay Boulevard, just past Liberty Avenue.

Residents were aghast at the prospects of a giant bridge hanging over the community and suddenly the plan to widen Woodhaven Boulevard, as it was now commonly referred to, looked pretty good. A few more years of controversy ensued, and several lawsuits were threatened, but by 1938 the city announced plans to widen the boulevard.

Eventually, the assessment for the project (the cost of which had ballooned in the 2 decades since it was first proposed) was distributed widely, with the City of New York picking up 75% of the cost, and the Borough of Queens picking up the remaining 25%. By distributing the costs this way, the residents of Woodhaven avoided picking up the lion’s share of the cost of a project that largely benefited others.

The final cost for widening the boulevard through Woodhaven was around $3 million, with most of that budget covering the cost of acquiring the properties marked for destruction. Many houses needed to be torn down to make way for the new lanes and several well-known structures, including Emanuel Evangelical and Reformed Church and the American Legion, were torn down and rebuilt elsewhere.

That fight over Woodhaven Boulevard may long be over, but a battle continues to this day over what to do with the amount of traffic traveling along it each way. And 70 years from now, regardless of the outcome of the current debate, it is very likely that residents will be fighting it out all over again.

As they say, the more things change, the more they stay the same.