The Renewable Rikers Act, a package of legislation that would transfer a portion of Rikers Island from the Department of Corrections (DOC) to the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) and initiate a study of renewable energy generation and storage there, was signed into law on Thursday, Feb. 25.

Mayor Bill de Blasio called it “an important, historic moment” prior to signing the bills introduced by Astoria City Councilman Costa Constantinides.

The package of legislation consists of two bills: Intro. 1592 and Intro. 1593.

Intro 1592 transfers jurisdiction of portions of Rikers Island that are not in active use as a jail site to the DCAS beginning on July 1. The full transfer of Rikers Island from DOC to DCAS will be completed by Aug. 31, 2027.

The bill also establishes a Rikers Island Advisory Committee that will make recommendations on the future uses of Rikers Island for sustainability and resiliency purposes. The committee will be chaired by DCAS and will include the Mayor’s Office of Sustainability (MOS), the Department of Environmental Protection, the Department of Sanitation, the Department of Parks and Recreation, as well as environmental justice representatives and members of the public who have been directly impacted by incarceration on the island.

Intro. 1593 requires MOS to study the feasibility of constructing renewable energy sources on Rikers Island, which could include wind or solar power, and battery storage facilities. The study will look at how renewable energy on the land can tie into the city’s long-term energy plan to phase out fossil fuels as part of the Climate Mobilization Act.

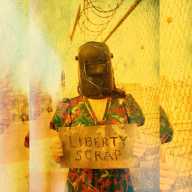

“For generations, Rikers Island has been a symbol the world over of our country’s failures to truly embody the principles of liberty and justice for all,” said Constantinides, chair of the City Council’s Environmental Protection Committee. “With the passage of the Renewable Rikers Act into law, however, we will finally close the book on the island’s brutal history. Now we can begin the work of fulfilling the promise of Renewable Rikers and bringing true restorative and environmental justice to the communities that have long suffered in its shadow. I thank the mayor for his support of the Renewable Rikers Act and to all the advocates whose work led us to this momentous day.”

The Renewable Rikers vision emerged from conversations about what the post-carceral future of the island may look like, and was led by survivors of Rikers who advocated for its closure in partnership with environmental justice leaders.

“The Renewable Rikers Act is an important step in delivering restorative climate justice and a clean energy future for New York City,” said Kate Gouin, acting director at MOS. “We look forward to studying and realizing the role Rikers Island and those impacted by our criminal justice system will play in our pursuit of a just and sustainable future for all.”

A 2017 report by Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform suggested critical environmental infrastructure may be the best use for the 413-acre island once the jails are removed by August 2027.

Constantinides partnered with the CUNY Law School’s Center for Urban Environmental Reform to expand on that suggestion. Professor Rebecca Bratspies, founding director of the CUNY Law School Center for Urban Environmental Reform, estimated using 100 acres of the land for solar energy and battery storage could lay the groundwork to justify closing every peaking power plant built in the last two decades.

According to a preliminary analysis by Sustainable CUNY, 35 acres of solar panels installed on Rikers Island would have a capacity of 14.6 megawatts and generate about 17.2 gigawatt hours annually. Meanwhile, 12 acres, or 4 percent of the island’s total area could potentially hold 1520 megawatts worth of storage — or about one half of the goal set for the entire state by the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

Advocates have long argued a Renewable Rikers is the best use for the land, given both its traumatic incarceration history and its existing environmental issues, as the island is predominantly landfill from ash and garbage with methane leaks being a persistent problem.

“It’s always been my belief that the island should be given back to nature to serve as a resource,” Eileen Maher, community leader at VOCAL-NY, said. “It’s stolen land from indigenous people, so creating a renewable resource doesn’t compensate for taking the land and using it for evil, but it does begin to right those wrongs and help the environment.”